What is a micro-hub and why are fleets moving away from pure van delivery?

Fleets that rely exclusively on large vans for door-to-door delivery in 2026 are bleeding money through inefficiency. The old model of driving a 3.5-tonne vehicle from a remote warehouse directly to a city center apartment is no longer financially viable due to congestion and regulation.

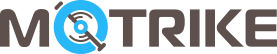

A micro-hub is a small, localized transshipment point—often a garage, a parking container, or a dedicated storefront—located inside the dense urban zone. It acts as a buffer. Vans drop bulk consolidated loads here, and cargo trikes perform the final short-range distribution. This decouples the "stem mileage" (highway driving) from the "delivery mileage" (stop-start driving), allowing each vehicle type to operate where it is most efficient.

Micro-hubs decouple long-distance van transport from high-frequency last-mile deliveryby cargo trikes, reducing congestion and delivery friction.

When I analyze fleet efficiency, I look for the "handoff point." In a pure van model, there is no handoff; the van fights highway traffic and then fights city traffic. This creates a scenario where a high-cost asset (the van) is stuck in low-value activity (looking for parking). By introducing micro-hubs, we treat the van as a feeder vessel and the trike as the precision instrument. This structural change is not just about being green; it is about maximizing the "packages per hour" metric that dictates profit.

Why are cargo trikes not simply smaller replacements for vans?

Many operations managers make the fatal mistake of copying van routes and pasting them onto cargo trike drivers. This approach ignores the fundamental mechanical and physical differences between the two vehicle classes, leading to immediate operational failure.

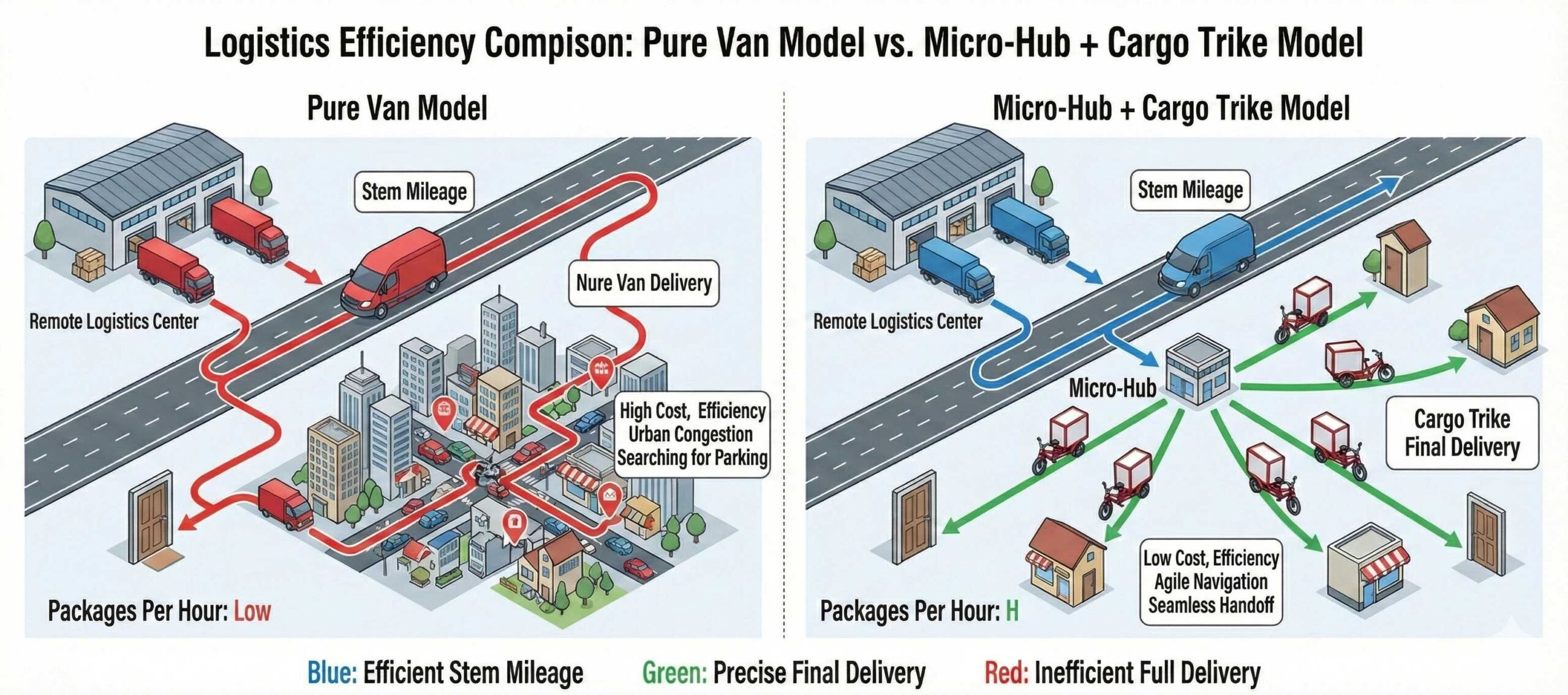

A cargo trike is not a small van; it is a high-frequency delivery tool. Vans are designed for volume and distance, utilizing momentum and high top speeds. Trikes are designed for agility, utilizing sidewalk access and quick acceleration. If you use a trike for long, straight-line distance, you waste its primary advantage—access—and expose its primary weakness—lower top speed.

Vans are engineered for volume and distance, while cargo trikes are optimized for agility and high stop density in urban environments.

When we engineer trikes at Motrike, we look at the "density of stops." A van is efficient when stops are 2km apart. A trike is efficient when stops are 200 meters apart. If you force a trike to drive 10km to deliver one package, you are destroying your margins.

The "Mini-Van Fallacy" often leads to overloading. A fleet manager sees a box on wheels and assumes it can take the same punishment as a Ford Transit. But a trike interacts with the road differently. It hits potholes that vans straddle; it mounts curbs that vans avoid. Treating a trike as a direct 1:1 replacement for a van without adjusting the route topology is the fastest way to break axles and burn out drivers. You must redesign the route map, not just swap the vehicle keys.

What duty cycle are cargo trikes actually designed for?

Understanding the specific duty cycle of an electric trike is the difference between a fleet that lasts five years and one that fails in six months. Ignoring these engineering limits results in overheated components and unexpected downtime.

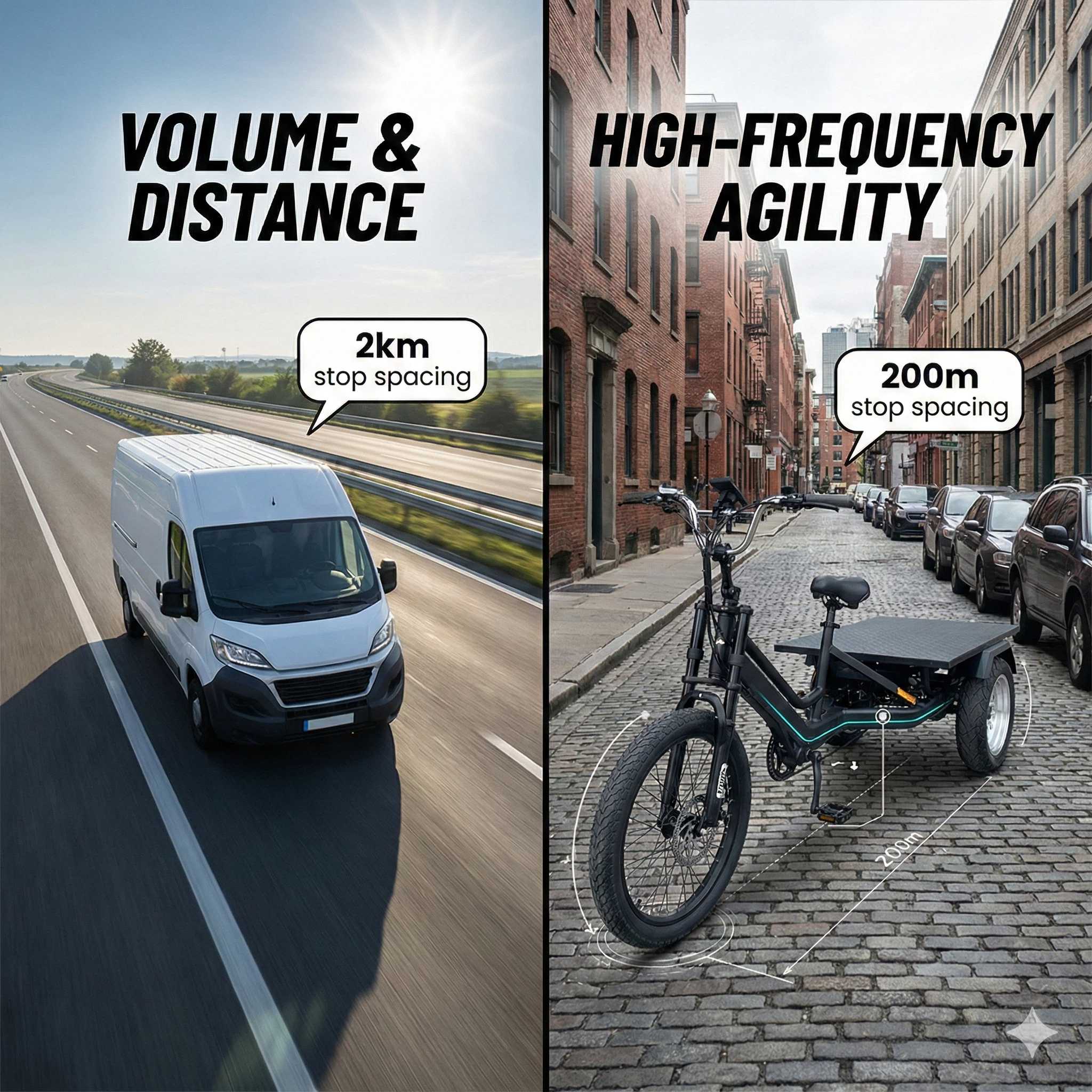

Cargo trikes are engineered for a "High-Torque, Low-Speed, High-Frequency" duty cycle. They excel in environments requiring constant stop-and-go motion, rapid acceleration from zero with heavy loads, and tight maneuvering. They are not designed for sustained high-speed cruising, which places a different kind of thermal stress on the motor and controller.

High-frequency stop-and-go delivery creates a very different thermal profile compared to continuous cruising, directly affecting motor lifespan.

Let’s break down the physics of the daily route.

In a proper duty cycle, the trike covers a small radius—perhaps 3km to 5km around the micro-hub. It performs 50 to 80 stops within that tight circle. The motor bursts to get the load moving, then rests while the rider drops the package. This "pulse" of energy allows cooling intervals.

The "Commuter" Error:

The operational failure happens when a manager assigns a "commuter" duty cycle. This involves driving the trike 15km at full throttle from the main warehouse to the city center before starting deliveries.

- Thermal Runaway: Sustained max throttle heats the motor windings without the "rest" period of a stop.

- Battery Sag: Continuous high-amp draw causes voltage sag, reducing the effective range of the battery pack significantly compared to stop-start usage.

At Motrike, we spec our drivetrains for the "last mile," not the "middle mile." If your operation requires long transit links, you are using the wrong tool. Put the trike in a van or trailer for the long leg, or establish a closer hub. Respecting the duty cycle is the only way to protect your asset.

How does poor workflow design overload batteries and motors?

Batteries and motors do not fail randomly; they fail because the workflow demands energy faster than the system can thermally manage. Poor routing software that treats a trike like a car is the silent killer of electric powertrains.

Poor workflow design forces the vehicle to operate constantly at its peak stress point. This includes routing trikes up steep inclines with full payloads or scheduling zero downtime for cooling. The result is uneven battery cell aging and premature controller failure, regardless of the component quality.

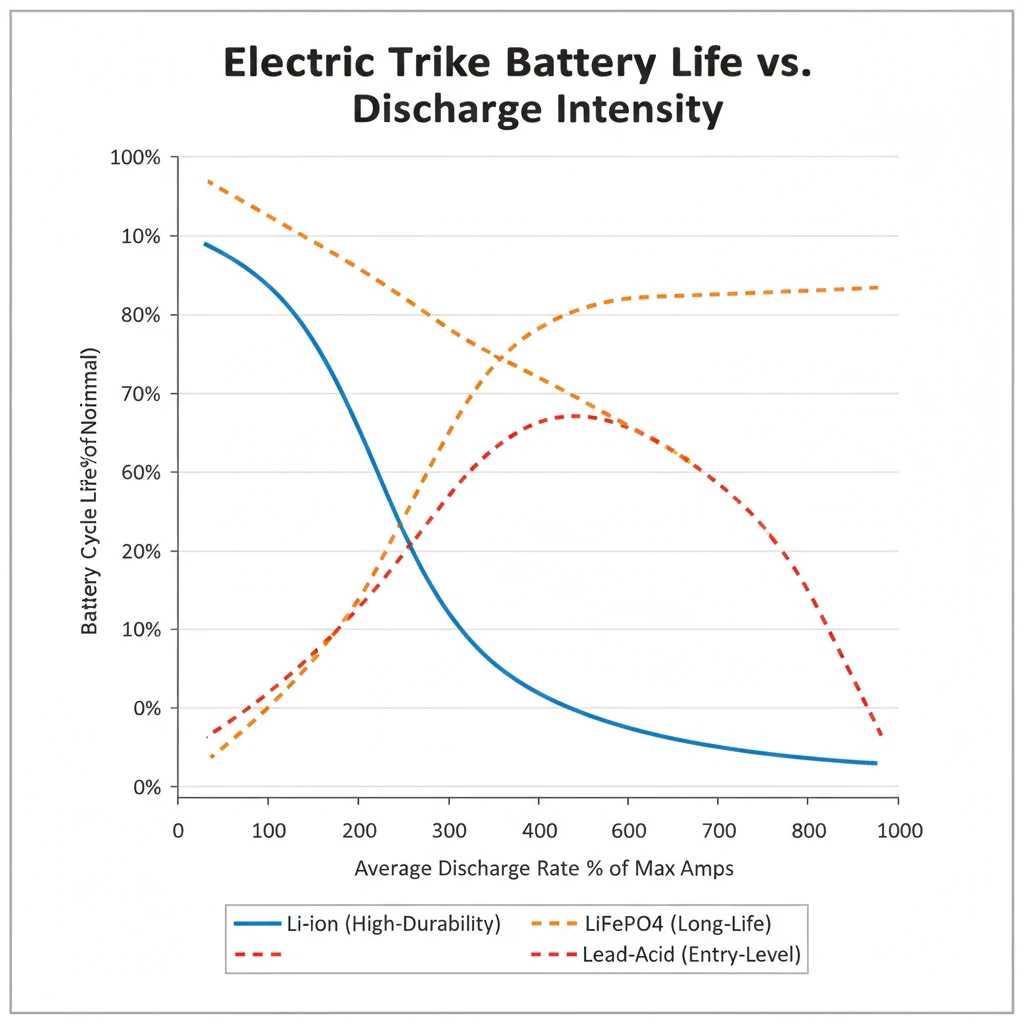

Aggressive discharge caused by poor routing and heavy loads accelerates battery degradation in commercial trike fleets.

I often see fleets using standard logistics software to plan trike routes. This software minimizes distance but ignores topography and load weight.

If you send a fully loaded trike (250kg payload) up a 15% grade for 500 meters, you are pushing the motor to its thermal limit. If the driver then immediately has to rush to the next stop at full speed, the heat never dissipates. Over time, this melts phase wires and degrades motor magnets.

Workflow Constraints for Longevity:

- Load Shedding: Operations should be planned so the heaviest items are delivered first. Carrying dead weight for the whole shift strains the suspension and drains the battery unnecessarily.

- Topography Awareness: Routes should be planned to avoid long, steep ascents when the vehicle is at max capacity.

- Rest Intervals: The natural workflow of delivery (parking, walking to the door, scanning) provides essential cooling time for the electronics. If you push for "zero idle time" by having runners meet the trike, you might ironically overheat the machine by removing its only rest period.

Why do swap-battery systems outperform charging in shift operations?

Plug-in charging is a logistical bottleneck that ties a fleet’s productivity to the speed of a charger. In high-tempo urban logistics, the vehicle must be moving to earn money, not sitting tethered to a wall.

Swap-battery systems allow for continuous 24-hour operations and eliminate the need for expensive charging infrastructure at every parking spot. A 2-minute battery swap resets the vehicle’s range instantly, whereas fast charging degrades cell life and still requires 2-4 hours for a safe full cycle.

Swap-battery systems eliminate charging downtime and allow continuous multi-shift urban delivery operations.

From an operational standpoint, the "Plug-in Penalty" is massive.

If you run a shift from 08:00 to 16:00, and the battery dies at 14:00, the day is over. The driver goes home, and the packages return to the hub. This is a failed route.

With a swappable system, the driver carries a spare or visits a swap cabinet. The route continues.

The Real Estate Factor:

Micro-hubs are small. Space is expensive.

- Plug-in Model: You need 10 parking spots with 10 charging points for 10 trikes. You also need a massive grid connection to charge them all simultaneously overnight.

- Swap Model: You need 10 parking spots (anywhere) and one charging cabinet that occupies 1 square meter. The cabinet charges batteries slowly and safely 24/7, reducing the peak power demand on the building.

We have moved firmly toward swapping at Motrike because it solves the "Grid Constraint." Many old city buildings cannot support the amperage needed to fast-charge a fleet. Swapping decouples the energy demand from the vehicle’s schedule.

What operational failures appear when vans and trikes share the wrong roles?

When a fleet manager blurs the lines between feeder and distributor, the entire network suffers. Using a van for single-item drops or a trike for bulk transfer results in a "worst of both worlds" scenario where costs skyrocket.

Operational failure manifests as "The Mobile Warehouse Paradox." This happens when a van spends 80% of its day parked while the driver walks, effectively becoming an expensive storage unit. Conversely, if a trike acts as a feeder, it spends 80% of its battery driving empty to the pickup point.

When vans and trikes are assigned the wrong roles, congestion, downtime, and asset damage increase across the network.

The most efficient fleets I work with enforce strict role discipline.

The Van’s Role (The Feeder):

The van should never stop for a single package. Its job is to move 100 packages from the outer warehouse to the micro-hub. Ideally, it should dock, unload 100%, and immediately leave to get another load. It is a pipeline, not a sprinkler.

The Trike’s Role (The Distributor):

The trike should never drive more than 2km without making a stop. Its job is to "explode" the density of the micro-hub into the surrounding neighborhood.

The Cost of Role Confusion:

- High Labor Cost: A van driver stuck in a city center achieves 6-8 drops per hour.

- High Asset Risk: A trike driver on a highway bypass risks accidents and destroys the drivetrain.

By forcing vans to stay out of the "last mile" and trikes to stay out of the "middle mile," you align the mechanical strengths of the machines with the economic realities of the route. It is not about replacing vans; it is about letting vans be vans and trikes be trikes.

Schlussfolgerung

Structuring a delivery network in 2026 requires acknowledging mechanical reality. Micro-hubs allow us to assign the right vehicle to the right friction zone. By respecting the duty cycle of cargo trikes and using vans strictly as feeders, fleet managers can lower costs, protect their assets, and increase delivery throughput.

Micro-hubs are only one component of a broader last-mile delivery system.A complete framework for cargo tricycle last-mile delivery is explained in our main guide.