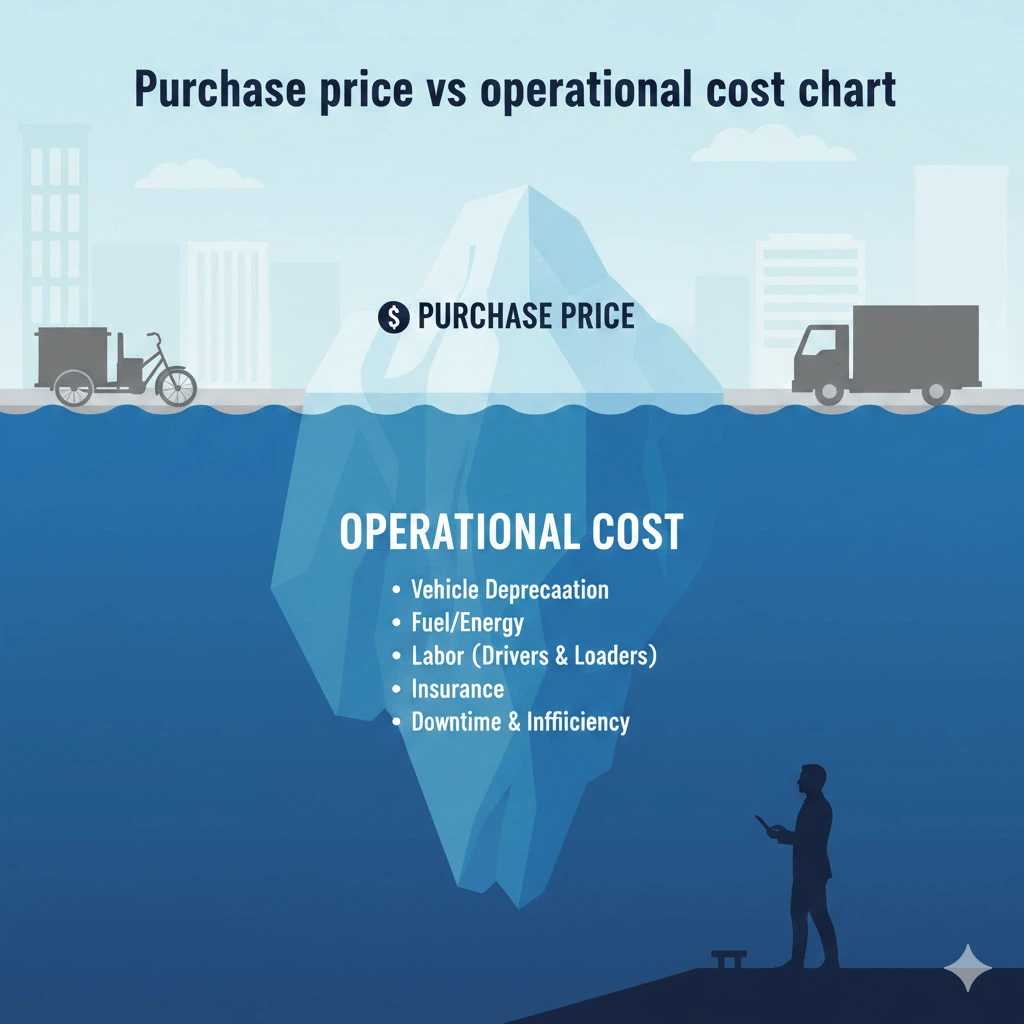

Why does purchase price fail to reflect real delivery cost?

Fleet managers often look at the spreadsheet sticker price first. However, relying solely on the acquisition cost ignores the daily operational friction that drains the budget in urban logistics.

Purchase price is a static, one-time expense, but delivery cost is dynamic. Real TCO (Total Cost of Ownership1) must include vehicle depreciation, fuel or energy, maintenance, labor, insurance, and critically, the cost of downtime and inefficiency. A cheap vehicle that cannot access the delivery point increases labor costs significantly.

Purchase price is a one-time decision. Operational cost compounds every delivery hour.

When I look at a fleet budget, I see two different stories,I approach this problem as someone who designs, tests, and runs commercial cargo trikes under real daily fleet conditions, not as an outside observer. One story is on paper, showing the asset value. The other story happens on the street, where friction, delays, and repairs dictate the actual profit margin. To understand the real cost, we must move away from simple asset comparison and look at operational reality.

What hidden costs appear when vans operate in dense city centers?

Standard delivery vans are designed for highways and wide avenues. When you force them into narrow, pedestrian-heavy city centers, operational efficiency drops immediately while running costs remain high.

The hidden costs include excessive fuel consumption from idling, accelerated wear on braking systems from stop-and-go traffic, and the "walking tax." The walking tax occurs when drivers must park far from the drop-off point, turning a 2-minute delivery into a 10-minute walk.

In dense cities, speed is access, not engine power.

We need to treat a delivery vehicle as a mechanical system interacting with the street infrastructure. In a dense city center, a van fights the environment. It is too wide for bike lanes and too large for curb-side parking. This creates mechanical friction and operational friction.

Mechanically, a combustion engine van operating in a city center is incredibly inefficient. It runs at low RPMs, constantly stopping and starting. This destroys fuel economy and clogs particulate filters. Even electric vans suffer here because they are moving 2,000kg of metal to deliver a 2kg package. The energy waste is massive.

Operationally, the "walking tax" is the biggest killer of efficiency. If a driver cannot park legally in front of the building, they park two blocks away. The vehicle sits idle, occupying space and burning time. If a driver costs €25 per hour, and they spend 15 minutes of every hour walking rather than driving, you are losing 25% of your labor budget to inefficient vehicle placement. This is a cost you pay every single day, and it never appears on the sticker price of the van.

How do parking fines and idle time increase cost per stop?

Many logistics companies treat parking fines as an unavoidable "cost of doing business." This is a dangerous mindset that erodes margins and accepts operational failure as standard procedure.

Parking fines and paid idle time act as a direct tax on every stop. A van that circles a block three times to find a loading zone burns fuel and labor time without generating revenue. This increases the effective cost per stop drastically compared to a vehicle that parks instantly.

If your route depends on finding parking, fines are part of the business model.

I never start a TCO calculation with fuel costs; I start with friction costs. In Europe and dense North American cities, parking enforcement is a major friction point. If your drivers are getting two tickets a week, you are not just paying the fine. You are paying for the administration to process that fine and the morale hit to the driver.

Consider the math of circling. If a driver spends just 4 minutes per stop looking for parking or circling the block, and they make 60 stops a day, that is 240 minutes. That is 4 hours of lost productivity per shift. You are paying a driver a full day’s wage for a half day of work.

Commercial tricycles bypass this friction entirely. They utilize sidewalk access or bike lanes and park directly at the doorstep. Physics does not care about your budget assumptions. A large object requires a large space to park. If that space does not exist, you pay for it in time (circling) or money (fines). Eliminating this "ticket tax" and "circling tax" instantly changes the unit economics of the route.

Why do cheap cargo trikes also become expensive over time?

Seeing the savings of trikes, some managers rush to buy the cheapest electric cargo bikes available. This usually results in catastrophic failure because consumer-grade parts cannot handle industrial workloads.

A cheap cargo trike becomes expensive through downtime. When weak axles, consumer-grade brakes, or under-powered motors fail under heavy loads, the vehicle stops generating revenue. The cost of replacing parts and renting backup vehicles quickly exceeds the price difference of a quality machine.

Downtime destroys ROI faster than fuel ever will.

I have seen this pattern many times. A fleet manager buys a fleet of €2,000 cargo bikes intended for grocery shopping, not logistics. They put 150kg loads on them and run them for 8 hours a day. Within three months, the spokes break, the frames crack, and the batteries degrade significantly.

This is where the "cost per hour" metric destroys the "cheap per unit" illusion. If your €2,000 bike is in the repair shop for two days a week, you are paying for a driver who has no vehicle. You are also paying for replacement parts that are not standardized.

Industrial delivery requires industrial engineering. Professional cargo trikes designed for daily logistics must use reinforced axles, motorcycle-grade braking systems, and heavy-duty differentials, because the mechanical stress of stop-start delivery under load will destroy consumer-grade components.because we know the stress these vehicles face. A commercial tricycle must operate like a forklift, not a bicycle. If you buy a toy for a tool’s job, you will pay double: once for the cheap bike, and again for the real one you have to buy later. Durability is the only way to protect your ROI in the long term.

How should fleets compare vehicles using cost per hour instead of cost per unit?

Comparing a van to a trike on a one-to-one basis is mathematically flawed. They operate at different throughput speeds in different zones. The correct metric is the cost per successful delivery hour.

You must calculate the total hourly operational cost2 (Vehicle + Driver) and divide it by the average number of deliveries per hour. In congested zones, a trike often delivers 30% more packages per hour than a van, making the cost per drop significantly lower despite the lower payload capacity.

When delivery speed and access are limited by congestion, cost per drop—not vehicle price—defines profitability.

Let us look at the real math. Suppose a delivery van costs €15/hour to operate (lease + fuel + maintenance) and the driver costs €25/hour. Total cost is €40/hour. In a congested city center, due to traffic and parking struggles, the van makes 8 drops per hour. The cost per drop is €5.00.

Now, take a professional cargo trike. The operational cost is perhaps €2/hour (depreciation + charging + maintenance). The driver still costs €25/hour. Total cost is €27/hour. Because the trike cuts through traffic and parks at the door, it makes 14 drops per hour. The cost per drop is €1.92.

Even though the van can carry more total boxes, it cannot deliver them fast enough in the city to use that capacity. The van is a storage warehouse stuck in traffic. The trike is a delivery tool. By shifting the metric to "Cost Per Hour" and "Cost Per Drop," the financial decision becomes obvious. In city logistics, time is the only unit that compounds.You are paying for speed and access, not just volume.

Table: Van vs. Trike City Center Cost Analysis

| Metric | Diesel Van | Commercial Cargo Trike |

|---|---|---|

| Total Hourly Cost (Driver + Vehicle) | €40.00 | €27.00 |

| Avg. Speed in Congestion | 12 km/h | 18 km/h |

| Parking/Walking Time per Stop | 4-6 minutes | 0-1 minute |

| Deliveries Per Hour | 8 | 14 |

| Cost Per Delivery | €5.00 | €1.92 |

When does a van still make sense, and when should cargo trikes take over?

Cargo trikes are excellent, but they are not magic. They have physical limitations regarding range and speed. A smart fleet manager knows exactly where the van’s efficiency ends and the trike’s efficiency begins.

Vans are superior for low-density routes with long distances between stops (over 3km) and heavy bulk transport. Cargo trikes should take over in high-density zones where stops are less than 1km apart and traffic speed is below 20km/h.

Vans dominate long-distance, low-density routes; cargo trikes take over where stops are frequent and traffic speed collapses.

There is a specific "tipping point" in logistics planning. I advise clients to use a zonal approach.

Zone A (City Center / Historic Districts): Here, the friction is maximum. Streets are narrow, parking is impossible, and pedestrians are everywhere. In this zone, the van is a liability. Cargo trikes are the only logical choice. The operational cost of a van here is unsustainable due to fines and delays.

Zone B (Suburbs / Industrial Parks): Here, stops are spread out by 5km or 10km. Speed limits are 50km/h or higher. A trike is too slow for this. It would spend too much time traveling between drops. Here, the van is the correct tool.

The most successful fleets I work with use a "Hub and Spoke" model. Vans or trucks bring the bulk goods to a micro-hub on the edge of the city. From there, the cargo trikes perform the final distribution. This allows the van to do what it does best (move volume over distance) and the trike to do what it does best (navigate friction). You do not have to choose one or the other; you just have to stop using the wrong tool in the wrong zone.

Conclusion

TCO is not just about the price of the vehicle; it is about the price of the friction the vehicle encounters. For city centers, heavy vans pay a high tax in time and fines. Choosing the right commercial tricycle removes this friction and lowers the cost per stop.This TCO comparison only addresses one part of last-mile delivery economics.

This TCO comparison only addresses one part of last-mile delivery economics.A complete framework for deploying cargo tricycles in last-mile logistics is covered in our main guide on cargo tricycle last-mile delivery.